Redemption Road – The David Pot Story

Redemption Road: The David Pot Story

There are some tough nuts to crack among humankind…from those who outright reject God—doing whatever seems right in their own eyes—to those who know the truth, yet allow shame and guilt to keep them from surrendering all. David Pot belonged to the latter category. And it would take decades of boozing and bouncing around the backsides of Red Bluff—until he was beaten and left for dead—for David to decide enough was enough.

Lord help me Jesus, I’ve wasted it so

Help me Jesus I know what I am

Now that I know that I’ve need you so

Help me Jesus, my soul’s in your hand.

—“Why Me”, Kris Kristofferson

In almost 60 years of living on this earth, David Pot has learned a thing or two. Unfortunately, the most important lessons he’s learned the hard way—in a classroom that none of us would want to be schooled in.

David’s graduation from that School of Hard Knocks was celebrated with him laying in a pool of blood on a cold, indifferent pavement in the city of Red Bluff. He doesn’t remember how he got there. Or who had beat him to within an inch of his life.

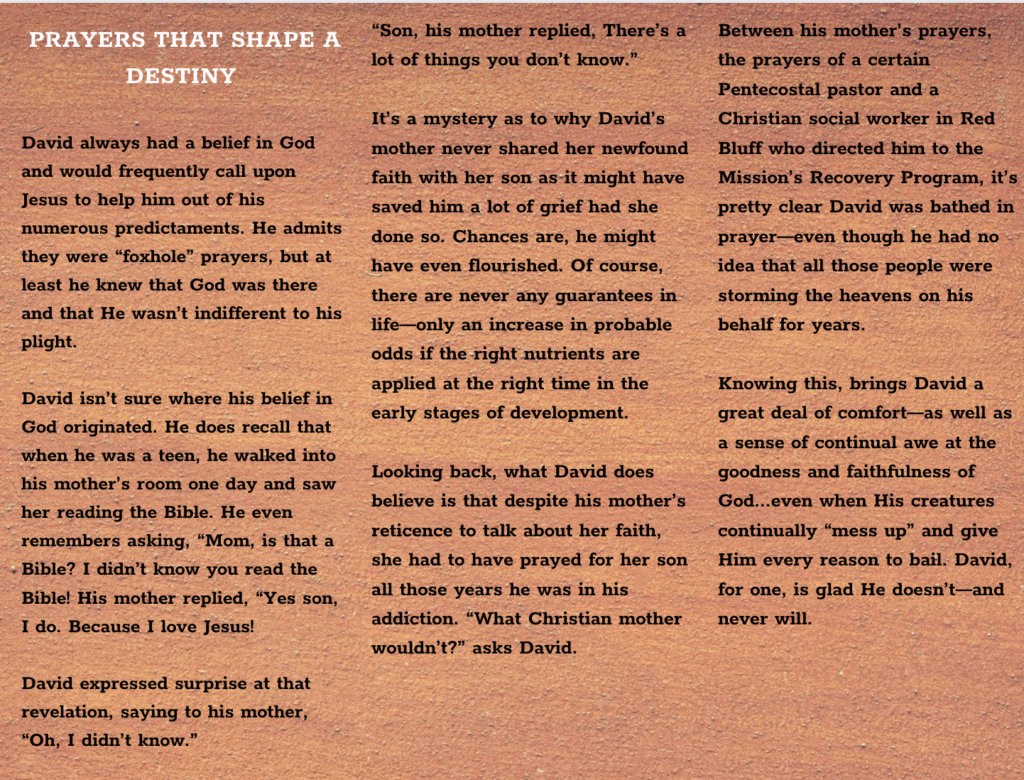

Pot’s beginnings were difficult. Although he was never physically abused, neither did he have much of a positive role model. Unlike his biological father who had abandoned David at birth, his stepfather, a full-blooded Cherokee, was physically present, and that was it. He was harsh, unyielding and a heavy drinker—at least on weekends when he would let loose after a week of truckin’ on down the road as a professional mover. His mother also drank heavily although she eventually quit on her own cold turkey. She also found God when David was a teenager which in retrospect David believes impacted his own “come to Jesus” moment decades later. Strangely enough, his mother never talked about her faith to her son. (See sidebar at end)

David speaks little about his parents, notably reticent to talk ill of them, which is fitting and right given the grace he himself has been the recipient of. But still, his parent’s addiction had a devastating impact on the young boy. Like all children in their formative years, David was molded in his parents’ image. Call it a “generational curse” or a hereditary disease, either way, booze was in his blood.

At eight years old, while his parents were ringing in the New Year with the customary holiday revelry, David took his first alcoholic drink from a spiked punch bowl. “I thought it was Kool Aid,” chuckles David. His parents later found he and his siblings passed out under the table. While the taste of hard liquor may not have been to an eight-year-old’s liking, drinking with his buddies when he reached his teens was a feeling he did like. And he kept at it from that point on—even when he no longer had anyone to drink with.

The Blue-Collar Drill

I woke up Sunday mornin’

With no way to hold my head that didn’t hurt

And the beer I had for breakfast wasn’t bad

So I had one more for dessert

– Sunday Morning Coming Down, Johnny Cash

Despite David’s inner vow to not go the way of his parents, by the time he was 17 and working for his father in the moving business, he was following the familiar blue-collar drill: Work hard all week and drink even harder on the weekend.

While he would do drugs intermittently, it was alcohol that became David’s primary numbing agent of choice. Despite his preference for booze, his first stint in in jail was due to a drug possession charge along with fleeing from an outstanding warrant.

By the time he was almost 60, David had done six prison terms. In between bouts behind bars, he survived on the street—in a self-constructed prison of addiction, and it’s close cousin, depression. For David, as it is with most addicts, it was an all-too familiar cycle of drugs, drink, and depression (not necessarily in that order) that’s hard to watch, hard to live and even harder to break.

Every Man for Himself

Fueling David’s depressive episodes was his feeling all alone in the world. And he pretty much was. All his family members were gone—including both parents and all of his siblings. He also never married or had children. He was the last of his family line. Even sadder, the sister he thought was still alive had passed away almost a year and a half before he even discovered she was gone, most likely from an alcohol-related illness, David conjectures. He didn’t want his sister’s fate to be his legacy, but he felt powerless to change that trajectory.

Instead, David continued to live for decades as a drifter—”with no direction home, like a complete unknown.” When not behind bars, “home” for him was wherever he happened to carve out a spot in parking lots, alleyways, under doorways, behind buildings, and sometimes out in the wild amongst the black oak, buckeye and pine forests of Tehama County.

For David, as it is for most people eking out an existence on the streets, it’s a harsh and lonely life. Friends, such as they are, are fickle and few. If you define a friend as someone who always has your best interest at heart, that would make that number, zero. For David, there were no friends, only “associates”. According to David, it’s a common term used on the street to describe what regular folk would call a friend.

A Friend Indeed

There was, however, one friend David could always rely on and that was Pastor Mike Cox, the pastor of Redemption Road Church in Red Bluff—an unassuming “little country church on the edge of town” filled with just the kind of praying folk you’d want storming the heavens on your behalf if you were in a bit—or a lot—of earthly trouble.

The good Reverend befriended him when David, by then a full-on addict, was in prison and then later on when he was released and living on the streets, drinking his days and nights away. When David was at his worst, the pastor would extend his best, demonstrating the love of God and “when necessary, using words”—which were usually words of hope from the Bible. In time, the pastor’s entire family embraced the social misfit, welcoming him into their home for meals and picking him up to take him to church, without once asking anything of him.

“His family kind of adopted me and I grew to really love them. He was also persistent in telling me about Jesus–how much he loved me, and how that only He could deliver me from my addiction. And I believed what he was saying 100%. The problem was, I was stubborn. I just wasn’t ready to surrender my life to God. And it’s sad, but that’s how much my drinking controlled my life.”

I’m the Boss of Me

When asked how it felt to be both homeless and an addict, David doesn’t mince words: “It felt free—like I was escaping my responsibilities and didn’t have to answer to no one. And the drinking just made it easier to do that. At the same time, it was frightening. When you’re homeless and you’re trying to find a spot to sleep, you’re always fearful of who’s going to be up to no good while you’re sleeping. So, you sleep with one eye open and one eye shut.”

Looking at it from the outside, that seems like a highly uncomfortable way to live. For most people, the prospect of always sleeping “with one eye open” is not worth the so-called freedom that a free-wheelin’ and free-spirited lifestyle brings. But for the men and women molded in that mindset, it’s an acceptable trade-off.

By his own admission, David was one of the latter. As he puts it, “I took the good with the bad…of living outside in the extreme cold or heat and all the other hardships I had to endure so I could be my own person, my own boss. I knew I was being drawn away from where I wanted to be in life, but my addiction just wouldn’t allow me to get there.”

David’s situation raises a question that many ask which is, “Do people living on the street even want to be housed?” “Some do, some don’t,” says David. “And I’m just guessing here, but I’d say over 60% don’t want to be housed. For whatever their reasons, they love being out there doing what they do. That was certainly my story. I mean, I didn’t, but at the same time, I did.”

“I won’t lie,” he continues. “The whole experience was terrifying—that’s the word I’d use. And I was always thinking to myself, ‘What a miserable life.’ And as I was soaking in my beer by the river, the pastor’s words would come to the forefront and I’d tell the Lord, “One day, Lord, I’m going to get out of this and I know you’re going to pull me out when I reach that point.’ And he would say to me, ‘Oh, son, you will find the bottom. And once you do, come and talk to me again.’”

God and all the fixins’

For David, it took a brutal beating by unknown assailants who had left him on the street to die, before he finally had that conversation with the Lord. A mysterious woman, or perhaps an angel, found his near-lifeless body laying in a pool of blood, and called 911. Taken to the hospital, David regained consciousness only to find himself in a hospital bed, attached to multiple medical cables. He had suffered a cardiac arrest and was barely hanging on.

“There I was laying in the bed all hooked up when suddenly I heard a voice speak to me even though there wasn’t anyone in the room,” says David. “And the voice said, ‘My son, have I got your attention now’? And I knew it was the Lord, so without skipping a beat I responded, ‘Yes, Lord, you do. You’ve got me, Father…so let’s do it!’”

David knew it was “do or die” and since he had just narrowly escaped being pushed through Door #2, he had no other choice. It was his George Bailey moment. It took only an instant for David to became “sorrowful as God intended”… a sorrow that would lead to repentance, or a change of mind and direction. By that definition, changing course for David meant not navigating the same waters as before, or in the same leaky vessel. Also not to be dismissed lightly was the reality that the Creator of the Universe had just spoken to him in an audible voice. It was all the proof David needed that he was still in the race—and that God’s love for him was far greater than the past that condemned him.

After being released from the hospital, David was directed to The Mission’s Recovery Program by a social services worker. Once there, he began doing some serious soul searching as he learned the tools of sobriety.

Resistance is Futile

David took full advantage of everything the Mission’s Recovery Program offered him, not resisting or chafing at the bit as some do, especially the younger students. He had one big advantage: he had come close to cashing in all his chips—dangerously close. Because of that, he was bound and determined not to play Russian roulette with the ever-decreasing years he had left on this earth.

David took full advantage of everything the Mission’s Recovery Program offered him, not resisting or chafing at the bit as some do, especially the younger students. He had one big advantage: he had come close to cashing in all his chips—dangerously close. Because of that, he was bound and determined not to play Russian roulette with the ever-decreasing years he had left on this earth.

Life is short, but regret is long. He wished the younger guys could know that.

“I had the benefit of knowing that addiction is a dead-end street. These young guys don’t necessarily have that understanding—they live in the moment. They can’t grasp the long-term consequences of their actions. But I was old enough to be living with a lifetime of consequences”.

“It works, man. Jesus works. The program works.”

Today, David is a graduate of the Mission’s Recovery Program and feels honored and grateful to be so. His life, as he puts it, has done “a complete 180.” He is sober and doing food pick up for the Mission—using his trucking background to shine the light wherever he goes—no matter how “insignificant” the task before him may seem.

A recent incident shows how seriously he takes the biblical admonition to “let your light shine before men.” While picking up a food donation at a local restaurant, David had leaned over to pick up a piece of trash. Observing that normally unappreciated act, a restaurant worker turned to him and said, “Thanks, man!” Not many people would show that kind of common courtesy just out of the blue like that.”

To a certain segment of Western believers with an upwardly mobile mindset, the act of picking up a piece of trash would hardly be on a spiritual par with being an influential Christian leader, or a stadium-level soul winner; however, to God, it’s exactly the same—perhaps even greater if we don’t think of the Kingdom as a numbers game, but rather as the posture of the heart.

It’s in that posture, the same posture a certain country church pastor from Red Bluff modeled to David for decades and still does to this day, that David practices. He makes sure he regularly checks in with “the guys” to see how they’re doing—and to encourage them to stay the course. Like his friend and former pastor, he’s persistent. For the first time in his life, he knows he has a purpose beyond just trying to make it through the day without having his stuff stolen, getting beat up or having that drink to fortify him. “It’s a wonderful feeling,” says David. “And it’s why I want to be that beacon of hope for the guys in the program. I tell them, ‘It works, man. Jesus works. The program works.’”

###